24. Why Do, How Do, What Do We Compose?: Revising and Remixing Your Ideas About Copying

What Writers Can Learn From Fashion Design

Composing and Assemblage

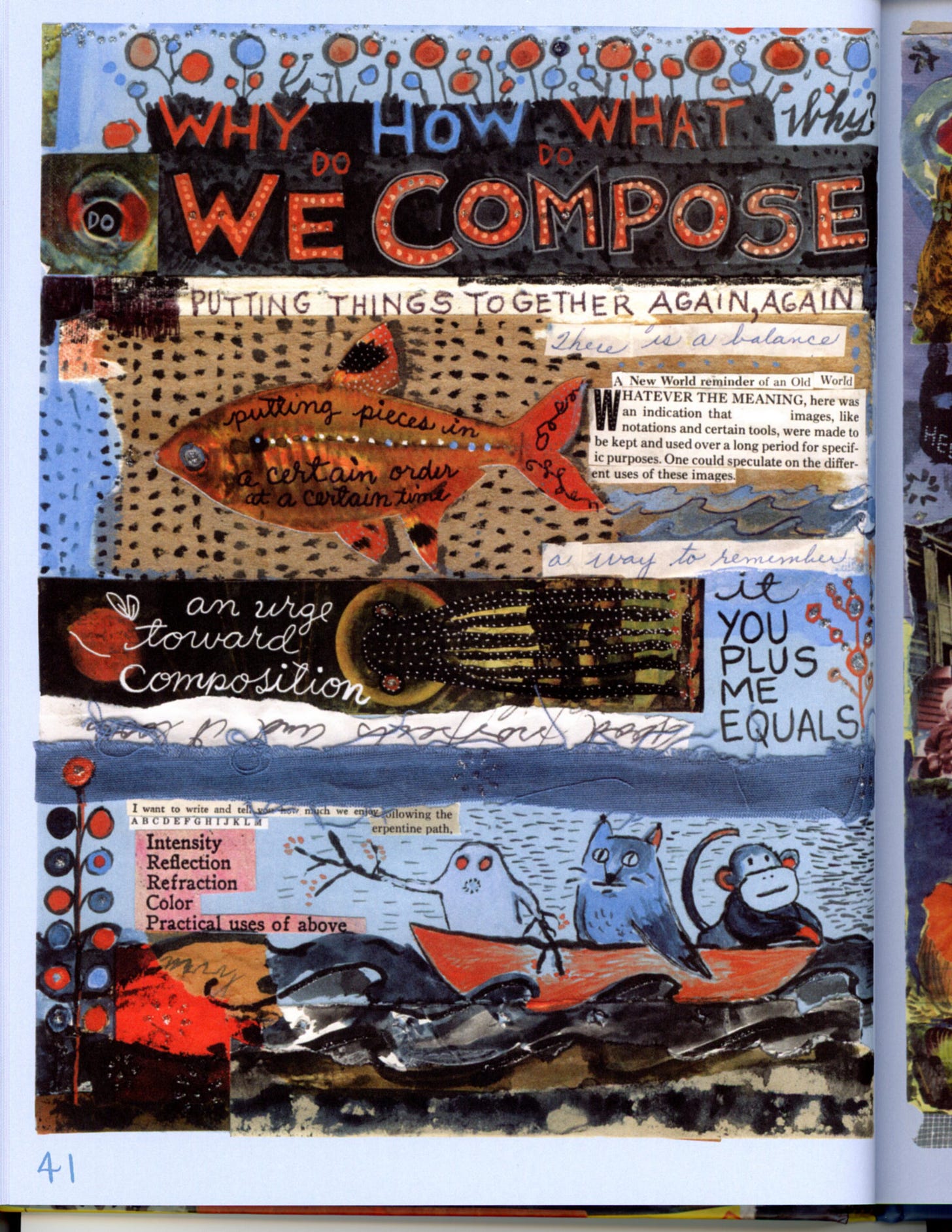

“Why do, how do, what do we compose?” Lynda Barry poses these questions in What It Is, a book about drawing and writing. This is where she calls composing “Putting things together again, again,” and “Putting pieces together in a certain order at a certain time.” The page where these elements appear is an assemblage or collage that includes ink drawings of recurring characters in orange, blue, and black, along with yellowed clippings borrowed from books or magazines and snippets from handwritten letters. She doesn’t just state her composing philosophy—she lays it out in front of our eyes. Now we have more than just a definition of the composing process; we also have an image of it.

“Again, again.” I understand this in at least two ways. One is that while composing, we are putting things together that once existed in different contexts—the bits of paper from letters and published works. These are being remixed and brought together in a new setting that gives them different meanings. In the process of assembling all of this, you reconsider what still belongs and where it belongs, and you consider what you might add to enhance the overall effect and meaning, a meaning that has probably changed since you began putting those things together. While working, you are reworking the work you’ve already done. You are revising, which is an essential byproduct of copying.

Hidden Layers, Revision, and Style

It’s useful to think of anything you read in this way. What you are seeing is the top layer, like with a painting in a museum, but there are many layers hidden underneath, without which the piece you are reading couldn’t exist. If that’s the case, then this gives writers free rein to do as they please, “independent of formal rules” as Robert Lang says, and to follow any scent and forge any trail you like. Like Barry, copy to your heart’s content. No harm done. You can paint over that part, or paint over the whole thing. That copying and those invisible layers are crucial, nonetheless. They gave rise to what came next.

Unfortunately, school gives many the impression that any “wrong” moves, even if early in the process, can be deal breakers and a waste of time and effort. Copying is considered a high crime. Not so, not if revision is at the center of how you think writing works. Think of Ann Berthoff’s circling back. You don’t always move ahead. You go back often, painting over sections you’ve already “finished.” Elana Ferrante describes it this way: “The way I read what I’ve done is by rewriting.” Writing, then, is a many-layered painting, even for the pros. You are, to paraphrase Barry, re-making something you made from things others made and, in the process, turning it into something of your own. This is how your style evolves from the styles of others.

During the composing stages, plans change. You thought you were doing one thing, but that turned out to be less important than what you are doing now. And that will likely change some more, probably due to something you copied and reassembled. One reason it’s important to give revision a prominent place in your concepts about writing is that, as Berthoff says, “we have to be alert to the fact that meanings can be arrived at too quickly, the possibility of other meanings being too abruptly foreclosed.” The same can be said for style and originality. If copying is prohibited, the possibility of developing a style of your own will be abruptly foreclosed.

Writing and Designing Without Limits

Limiting ideas on what revision is and does limits your ability as a writer. This means there should be no limits. Part of writing and rewriting is copying and remixing, or, to put it more politely, making use of “intertextuality.” In “The Streets of Rome: The Classical Dylan,” Richard Thomas analyzes Bob Dylan’s re-use of lines from Virgil and others in his songs and how placing them in new contexts gives those lines new meanings. This is what Barry does with her drawing/painting/pasting assemblages. It’s Lang’s “make a change; see the result.” Copying, if done well, is not plagiarism, which I grant you may sound confusing. Plagiarism is copying but without remixing and revising, all without acknowledgement or attribution and, to paraphrase Lawrence Lessig in Remix, without saying something the borrowed pieces didn’t say.

Counterintuitively, Johanna Blakley says that lax copyright laws in the fashion industry don’t hurt designers but rather help them to thrive. The prevalence of copying forces designers to “up their game” and to come up with more innovative designs. In addition, like Barry said of her copying habit, this leads designers to come up with a “signature style” that is immediately identifiable to those in the know. People can recognize the influences that you’ve copied (ahem, borrowed) and remixed to come up with your style.

Different disciplines have different rules for how attribution and compensation should work, but the point is, whether it’s music or literature or comedy or fashion, copying is part of the process. So copy and remix to your heart’s content, but do it in the way Lang suggests for origami design:

If you are a beginning designer, you should realize that no design is sacred. To learn to design, you must disregard reverence for another’s model, and be willing to pull it apart, fold it differently, change it, and see the effects of your changes.

Copy it, then make it your own. When writing, don’t let the stigma of copying stop you from creating. If it turns out well, great. Next, show us your influences and where they came from so we can copy them, too (and maybe even copy your copying to help us develop our style and voice).

Plagiarism and Advancement

In the previous newsletter, I discussed a beautifully problematic student essay, and one of the problematic things about it was its plagiarism. The writer used words from others without quoting or documenting that material, but it didn’t bother me.

I didn’t want to crack down on the “incorrect” writing and likely plagiarism. The language appropriation may have been necessary to get him to this point because he is reaching “beyond his present abilities,” as Paul Williams says. As a writer and as a fairly new English speaker, he’s reaching “beyond what he’s sure he can do and into the unknown,” which is not only brave, but is exactly what I’m looking for.

In this case, I see it as an essential step in the writer’s progress. His copying, however crudely executed, made it possible for him to say something only he could say. You might even say the student’s views on how the writing process works, though not fully formed, are advanced. In another newsletter, I showed how Barry’s copying was essential to her development in drawing. Because of all that copying, she says, “I can copy anything into my own style.” This is like Blakley’s “signature style” idea, which also comes from copying.

My question is, why penalize writing students for using the creative strategies that the pros use? Permitting students to use those strategies gives them a taste of the same mental processes that the experts experience as they create, allowing their brains to develop similar abilities to ruminate, notice things, compare, and make connections and associations that otherwise would not occur to them.

Rather than spending time on surveillance and detection, writing instructors should include lessons in copying. Give students the same tools that helped others reach beyond their abilities and enabled them to find their way. After some practice with this, there will be time to teach student writers how to reveal their influences to their readers so they can be influenced by them, too.

Notes

Next, more about the wonders of plagiarism.