2. Make a Change; See the Result, or What Do You Think You Are Doing?

Ant Behavior, Origami Design, and Writing

Put yourself in an ant’s place. You are highly active in pursuit of a specific goal, foraging for food, while being unaware (apparently) that you are accomplishing something else—contributing, via pheromone release, toward building an elaborate network of resource procurement that grows and sustains a superorganism. Deborah Gordon, an expert on ant colonies, says some of what she’s learned about ant behavior can shed light on human behavior. Like ants, she says, “every person always thinks they know what they’re doing, even if they’re wrong.” Researchers (like the choreographer in “The Dance”) are able to step back and see the larger picture, see what the ants are really doing.

Something similar happened in an undergraduate writing workshop I attended. Often when reviewing classmates’ work, we would catch each other writing brilliantly in ways the authors themselves may not have noticed. When one of us discovered something like that, say in someone whose last name was Miller’s paper, we said, “Ah, how smart is Miller?” The How Smart question became a supreme compliment. It meant you were writing well, accomplishing something noteworthy, even if, like some dutiful ant, you thought you were doing something else.

My takeaway from these peer review sessions was that sometimes when you are putting words to the page, you reach beyond your intention and exceed expectations, and sometimes you are doing this without knowing it. This means, when I’m writing and things are going well, I’m smarter than I really am. The process takes over, like a software program kicking into gear, but it sometimes takes a Gordon-like observer to notice what’s happening. Occasionally, others need to point such things out to you (unless you are a genius, of course).

For me, the act of writing raises questions about intelligence, ability, talent, and performance—where they come from, how they are defined, and how to tap into whatever it is about writing that seems to bring these qualities about by accident at times.

Most writing/composition texts I read in my student days were of little help. (I’m sure they are better now . . . ) Those texts placed a heavy emphasis on The Well-Made Plan. You could get the impression that writing was as simple as following a recipe (but a recipe for something no one would want to eat).

The well-made plan never worked for me. It left me defeated before I started. Getting a good idea was too much pressure. Smart people get good ideas, not me. That’s why they get them—because they’re smart. I concluded that writers were just some exotic species apparently unrelated to me. As a result, I did what was expected and wrote about typical English paper topics and said the typical English paper things and received the typical blah, blah, blah English teacher comments about organization and transitions and the importance of not straying from my thesis. My grades were fine, but it all left me uninterested and uninspired. However, there were these mysterious moments (interestingly, usually not in English class) when I wrote something that I liked, and it always surprised me. This left me in a strange place: maybe I liked writing, so why did I hate it in English class?

Then in graduate school, I suddenly found myself in the tough spot of needing to teach writing to college students even though I didn’t have any interest in doing such a thing, nor any idea how to do it. During this time, I read about composition theory, a field I hadn’t known existed until the week before I started teaching, but that nevertheless has been invaluable to me as a writer and teacher ever since. This taught me about some ways students learn. Though it was and continues to be inspiring to read the research about writing pedagogy, for me, something was missing (besides crisp, engaging writing, lol). Being a creative writing student, I wanted to know more than what the composition researchers were telling me. Here was my question: How do the well-known writers—you know, the big guns—do what they do? In an attempt to find answers, I read interviews and books where famous writers talked about their process. Kind of a mistake, to be honest.

They had okay but boring advice—you know, read a lot, write every day (yeah, right), keep a journal (sure), find a writer’s group (easy for you to say), write at the same time every day (because I have nothing else going on, I guess). These answers, with some exceptions, felt deflating and of limited use and seemed at least cliché adjacent. Creative types, I discovered, were not much help, either, often speaking of inspiration, of intuition, of the Muse, of having a feel for what they do, sometimes using words like knack or gift—a feel for dialogue, a knack for detail, a gift for metaphor, or maybe an intuitive insight that came out of nowhere or in a dream. Gee, thanks. That’s the problem with geniuses. They can be so clueless!

Unfortunately, the message I got from most creative types was they had something that I didn’t. (I knew it.) Eventually, however, I discovered why it’s so difficult for talented people to explain their successes.

As my interest in writing merged with a sudden urgent need to learn how to teach, and since I found many writers’ explanations so underwhelming, in desperation, I developed a habit of trying to find information about how writing works by reading about how other things work, things like painting, biology, computers, animal behavior, coping saws, you name it. It was in a book about origami, of all things, where I found one of the most useful explanations I’ve seen of the creative process.

Most origami instruction is about how to fold a single sheet of paper very precisely based on a few simple folds (mountain folds, valley folds, creases), with no cuts, resulting in a crane or another traditional figure. Yet origami artist and mathematician Robert J. Lang makes an important distinction, focusing on design and how it happens. He says, “‘How to fold’ is rarely ‘how to design.’” School (including English composition class, at least in my experience) was mostly about getting the folds right. That could hold my interest only so long. Somehow in that undergrad writing workshop, though, we, by accident, became more than mere folders. But how did that happen? How did we learn it?

Lang says it’s possible to teach someone how to fold a crane, but it’s nearly impossible to teach that person how to design a new figure. Designers, he says characterize design as “intuitive,” done by “feel.” (Here we go again, I thought.) But, instead of just saying it’s a gift and stopping there, Lang pushes for more. This “feel” business he’s talking about—it’s not a gift after all. It just feels like one. It doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s something you make. Lang explains:

Many of today’s origami designers develop their folds by a process they often describe as intuitive. They can’t describe how they design: “The idea just comes to me.” But one can create pathways for intuition by starting with small steps of design.

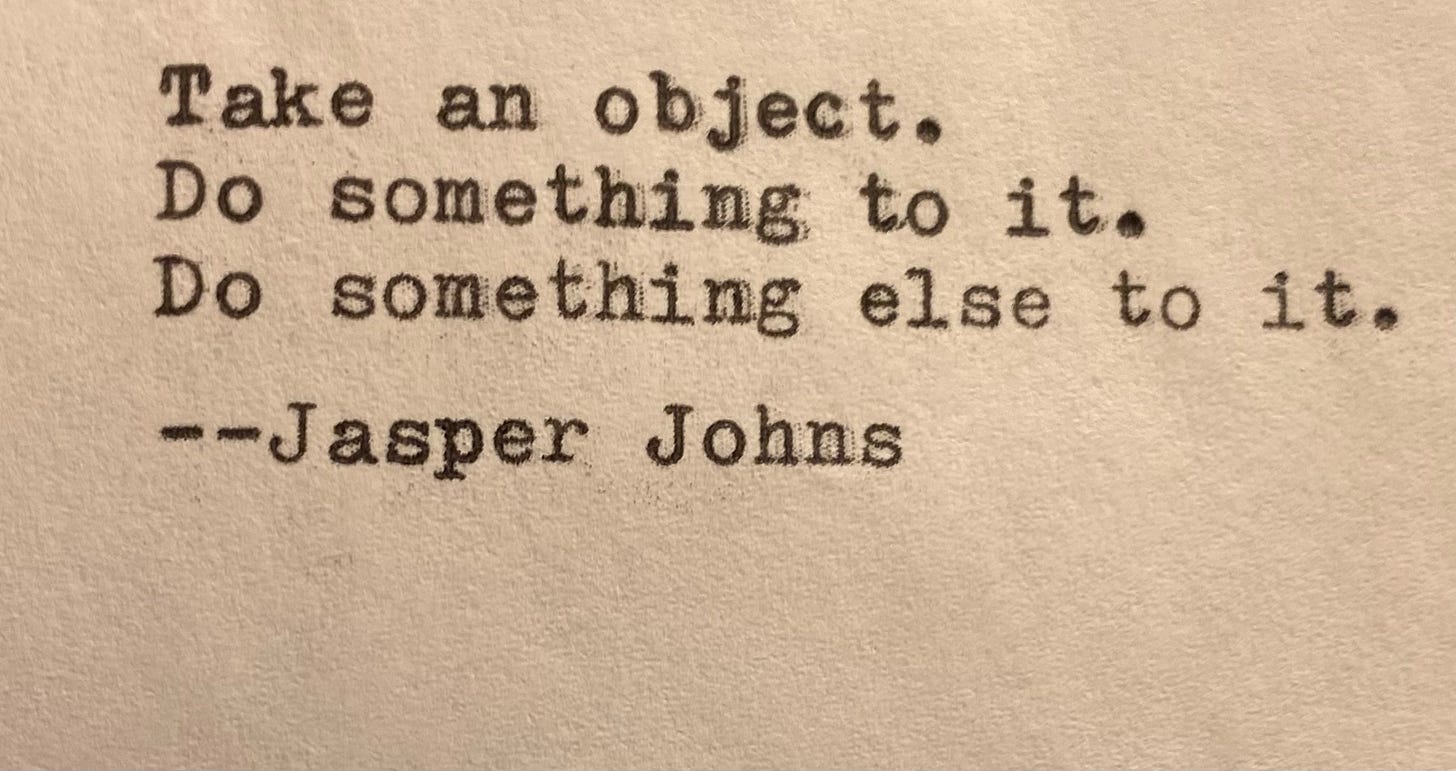

What are these steps and where do these pathways and this sense of feel come from? Lang says, “Design can start simply by modifying an existing fold. Make a change; see the result. The repeated actions build circuits in the brain linking cause and effect, independent of formal rules.” He adds, “Small ideas lead to big ideas; the concepts of design build upon one another.” This process is what makes it possible for an individual designer to have a breakthrough moment and suddenly see new possibilities.

The process Lang talks about comes over time and in specific stages, what he describes as “playing around with paper” which eventually evolves into “more directive playing” and finally into “systematic folding.” For ages, Lang concentrated on playing with paper unaware that he was rewiring his brain. These simple steps he followed created the “pathways for intuition” he mentions. (Think Mozgala and Rogoff’s “paths of communication.”) When creating a piece, Lang doesn’t follow a recipe or copy someone’s template precisely, he says, but rather dips into the “bag of tricks” he has accumulated through countless hours of playing and experimenting. After a while, that bag of tricks begins to feel like instinct because the tricks become moves you no longer need to think about. They seem to flow out of you. Congratulations! You now have a knack for design. Inspiration is rarely lacking. The Muse, once AWOL, are suddenly hanging out nearby on the regular.

Though origami design is a creative activity and one that, in Lang’s words, “cannot be taught directly,” he shows how "it can be developed through example and practice." That means there’s hope. Even for me. Stuff happens while playing that can’t happen when you are simply thinking or planning or following directions.

Writing, they say, also cannot be taught directly but like origami, it can be developed in similar ways. Rather than falling back on all the old writing advice chestnuts all the time, you can focus on similar stages to what Lang suggests: a lot of play—I mean a lot—followed by directive playing, followed by a more systematic experimentation, all done with a spirit of inquiry and no pressure. This is how you will build pathways and add to your growing bag of tricks.

For me and for my classmates in that undergrad workshop, the most interesting stuff happened while we were playing around with ideas and interpretations for our papers and when our professor stepped back becoming just another voice in the room. Nothing was too outlandish or off-limits. We were enacting “Make a change; see the result.” Here is where we developed a reader’s eye for possibilities. Along the way, from writing and observing how others wrote, we came across things to add to our bags of tricks. This is where others caught us being geniuses in ways we were too dumb to notice, probably because we were so intent on making a perfect crane that we couldn’t see the elephants and orchid blossoms right in front of our eyes. Like Gordon’s ants, we thought we knew what we were doing, but we were wrong. Playing around like this led our group to novel insights which often caused us to change direction. (I see what I can do now.) This was how we built our pathways and developed new abilities.

It was a gift.

Speaking of Elephants and genius, let’s talk about the elephant in the room: genius and what it has to do with writing.

Notes/References

Robert J. Lang’s Origami Design Secrets

The Deborah Gordon quote comes from Steven Johnson’s Emergence