Writing While Grieving 8: Paradise Lost, Milton, Dante, and My B

Sha-La-La-La-La-La, Live for Today

On the one-year anniversary of my wife’s death.

I think I've come to see myself at last

And I see that the time spent confused

Was the time that I spent without you

The following is a remix along with newly added parts of three speeches I gave, two of which I never wanted to give: one at my wife’s celebration of life, another at the recent naming ceremony for my neighborhood library’s children’s room, and another from a 2023 conference presentation where I first told the story of how my wife guided and influenced my teaching career and my views on writing.

I'll be your mirror

Reflect what you are, in case you don't know

I'll be the sun, the wind, and the rain

The light on your door to show that you're home

B and I met one summer evening in 1973, though only for a few minutes. She was in town for a summer job, but not for long because summer was almost over. That winter, I could not stop thinking about her blue, forget-me-not eyes, her long, dark, wavy hair, and, of course, that smile. One night, I dreamed of her and woke up saying her name. I found out from a friend that she was two years my senior. I didn’t stand a chance. Still, I hoped she would come back.

I waited and watched. Then, on June 28th, the following year, there she was. We were both with friends, but before long, inexplicably, I found myself alone with her. I learned later that she had convinced everyone else that they should suddenly remember how they had somewhere else they needed to be.

Probably at best, it will only last until Labor Day, I figured. After all, she was headed for college, and I still had two years of high school. As we got to know each other that summer, though, she seemed to see something in me no one else saw, that I couldn’t see, myself. When that happens, it’s a powerful thing. Whatever she saw in me, I resolved to do my damnedest to live up to it.

Somehow, we were already married.

Before long, though, she was 600 miles away attending college, and I was stuck in high school and my cold and desolate hometown. During the long months apart, writing kept us together. We wrote letters almost every day. She attended the college where her parents worked. Her father was a minister and a professor, and her mother worked in the registrar’s office. The school was a forty-five-minute drive from the nearest anything. I lived in the sticks, but this was something beyond. The school was religious and conservative, and it also had weird rules, but that didn’t stop me from applying there. In fact, it was the only school I applied to. (Yeah, don’t do that.) Though my majors were in English and writing, my true major was in B. Through example, she showed me what it meant to be a student and a reader, and after a while, I sort of caught on.

We married too young (again, don’t), but we’d been going out for four years and weren’t allowed to live together, so we tied the knot. Waiting for me to graduate, B worked at the college library. Throughout her life, wherever she was, people congregated, and our apartment became a kind of salon where students gathered, where class and book discussions spilled over sometimes into the wee hours.

Just as I’d followed her to college, I followed her to graduate school, where she studied library science. The key moment in my graduate career came not from my professors but from B. I had to teach English composition classes, which, as a student, I had always hated. Plus, I had to take a year-long seminar on composition theory from an absolute bear of a professor. There was one book from that seminar, though, by Ann Berthoff, that made me take notice, so I read some key passages to B.

Meanings don’t just happen: we make them; we find and form them.

It's often said that people learn to write by writing. . . But writing can't teach writing unless is understood as a non-linear, dialectical process in which the writer continually circles back, reviewing and rewriting. . .

When I finished, she pulled a book off the shelf and said, “You might want to take a look at this.” She handed me a book about Norse mythology open to a chapter on the Valkyries, Norse god Odin’s battle-maidens, whose task was to fly over earthly battlefields and select the most skilled and valiant soldiers to add to Odin’s army for the upcoming battle with the frost giants. The language in that mythology book and Berthoff’s language echoed each other in remarkable ways. The myth enacted Berthoff’s make, find, form, and reform. Each day, the Valkyries selected soldiers from Earth to be slain and raised them to Odin’s kingdom, Valhalla, and added them to the ranks of Odin’s army. In Valhalla, they held daily practice battles. In this way, each day, the army was found, made, reformed, and revised.

In an instant, B had shifted my worldview about writing and teaching, allowing me to see how much they were entwined. I didn’t know it yet, but with her breezy, offhand, deeply intelligent, and highly informed recommendation, she had just handed me my career. Not only that, like some kind of wizard, she had once again opened a new world to me.

This is what conversations with her were like. It was my favorite thing in the whole world. So if you are looking for a partner, I have some advice—if at all possible, marry a librarian.

Next, I followed B to the city where I now live so she could begin her library career. By the time our daughter was born, B had been a children’s librarian for seven years—lucky for our girl, who got daily private storytimes, crafts, and songs. No wonder her first word was “book.” It was a joy to watch the special bond between them develop and then how it carried on into our daughter’s adulthood. They were inseparable. So, if you can’t marry a librarian, then do whatever you can to come back in another life as the child of one.

B worked at our city’s library for 41 years, but her library career was longer than that. Before grad school, she worked in her college’s library. She also lived next door to a public library from age 11 through 15, where she first learned the trade as she eagerly volunteered there, shelving books and covering for staff breaks. It all began, though, when five-year-old B visited a public library with her father, got her first library card, and checked out the picture book, Petunia, by Roger Duvoisin.

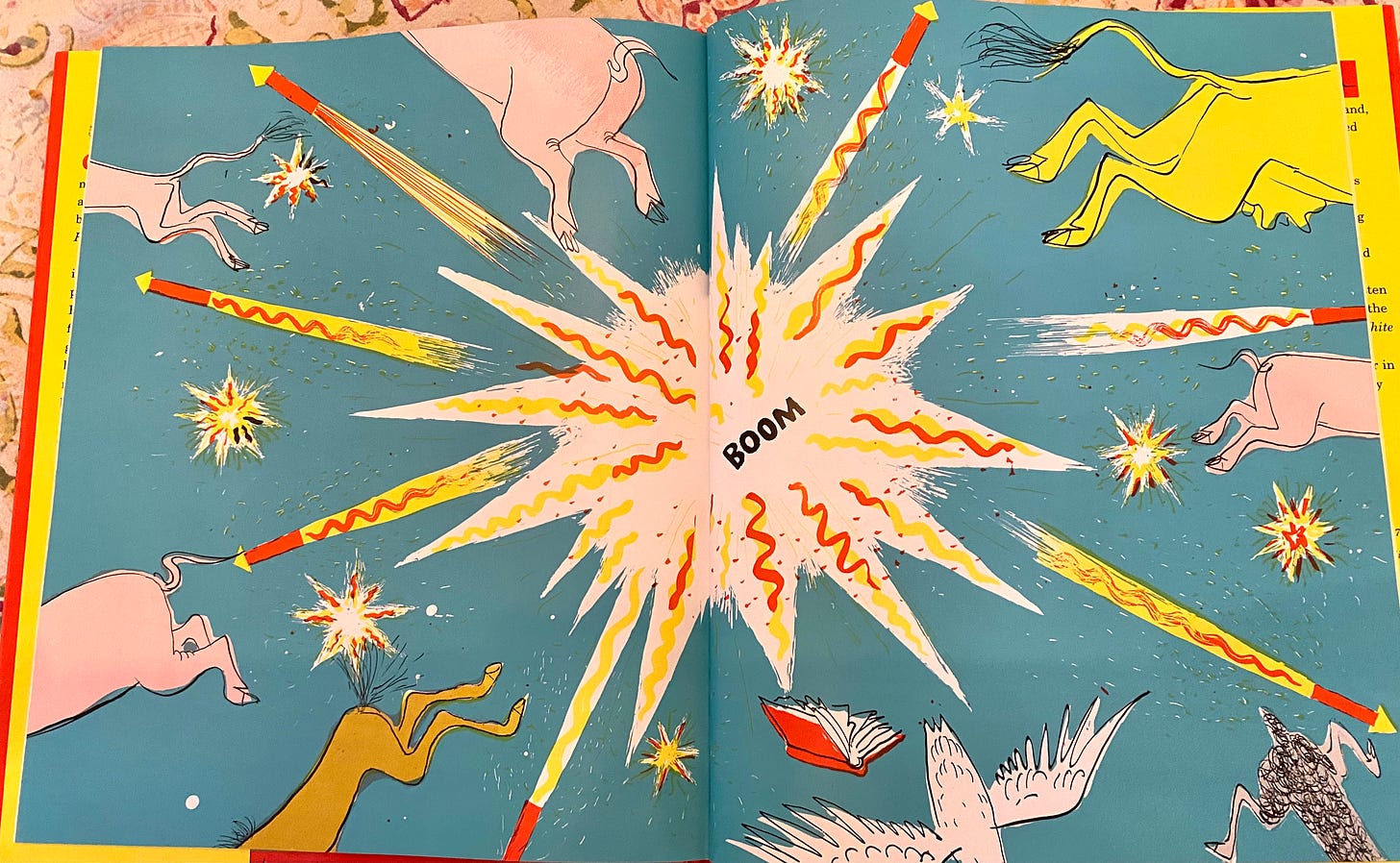

Petunia is the story of a silly goose who found a book in a meadow and thought that carrying the book around would make her wise, not silly. Unfortunately, the wisdom she offered to her barnyard friends always turned out to be disastrous, like when her friends found a box full of fireworks and Petunia said the box contained candy.

Only later did Petunia realize that books couldn’t make her wise unless she learned to read them, not just carry them, so that’s what she set out to do. The story concludes, “Then she would help make her friends happy.”

B grew up in the church, but it was during that library visit that she found her congregation. What must it be like to know what you want to be from age five and then to live out that childhood dream, a dream to make others happy, and on top of that, to be so amazing at it?

My daughter shared a passage written by Jenny Slate with me. Slate’s recollections of her mother remind us of B. The passage reads, “The more you give, the more you have, the more new things you are a part of, the more you are truly alive.” To paraphrase Slate, my daughter and I live in awe of B’s style of motherhood and companionship, her endless curiosity, and her unique humanity.

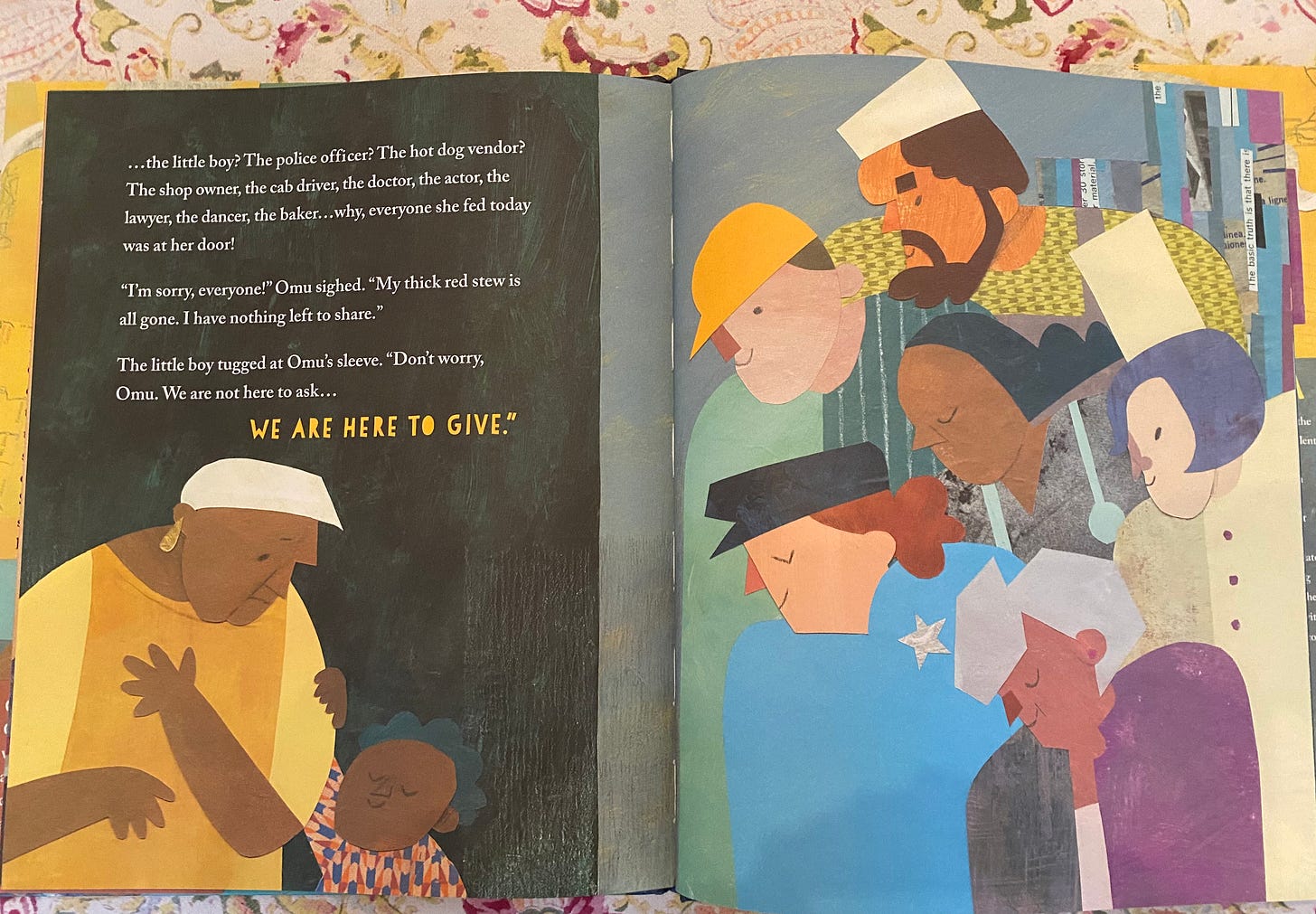

At B’s library-centered celebration of life, there were fingerplays and songs and a reading of Oge Mora’s picture book Thank You, Omu. Omu gave away all of her delicious, thick, red stew that she worked so hard to make—which is so B. In Omu’s case, her community thanked her for her generosity by giving her “the best dinner she ever had.”

Reading that story at the celebration was an inspired choice because it captures B’s giving heart, and the naming of the children’s room after her, like with Omu’s story, exemplifies B’s the-more-you-give-the-more-you-have worldview.

B and I had planned to retire together last summer, but I had my doubts that it would happen. It was one of those Sure, I’ll-believe-it-when-I-see-it situations. In a sense, it fits that she never retired, that she was a librarian until the end.

Though I initially doubted B and I would make it past Labor Day, 1974, we were together for just shy of fifty years. As our friends know, we were an odd couple. She had a sunny disposition, while mine comes with the threat of clouds. I suspect she kind of liked that, though. In other words, despite our odd-couple status, we were a pretty good team.

Singer Nick Cave called grief “the terrible reminder of the depths of our love, and like love, grief is non-negotiable.” My daughter and I have lost our best friend, our fiercest champion, our guardian angel, our shelter from the storm. Even though we don’t know how to go forward from such a loss, B would want us to figure it out, so that’s what we’re going to do.

She was our hero and our guiding light, and she continues to be. Though we are lost without her, she left us endless examples of how to live. Her wisdom, unlike Petunia’s early advice, was empowering and inspires us still. Though a year later, this world without her remains unrecognizable to us, my daughter and I take comfort in knowing that we do not bear this alone. The amazing communities she built at the library and in our neighborhood remind us of how many others share a deep love for B and are touched by her exceptionally well-lived life and her extraordinary ability to make her friends happy.

There’s a quote from Henry James by way of James Baldwin, in an essay my daughter texted me, where he says, “Live—live all you can. It’s a mistake not to.” My daughter said, “It sounds like Mom.” There’s a kind of companion quote from Middlemarch, one B wrote down in a journal and that was printed in B’s handwriting in the lovely bookmarks distributed at the celebration. It says, “What do we live for if it is not to make life less difficult for each other.”

For B, living life to the fullest and making things less difficult for others went hand in hand. She was an artist at this. It was a thing to behold. We knew she was important to a lot of people, but now, because of all the testimonials since she left us, we see the true extent of it, and we could not be more proud of her. As my brother said, “She was a wonder.”

I want to close this newsletter by elaborating on the above quotes from Henry James, George Eliot, and Jenny Slate, but I want to do so by talking about Milton and Dante. The title of this newsletter is “Paradise Lost.” I used that title because that’s what my daughter and I have lost, but also because B loved Milton. I’ve been thinking of Eve and how she was portrayed by Milton, and I’ve been thinking as well of Dante’s Beatrice and her role in guiding Dante through Paradiso in the Divine Comedy.

In his excellent article, “My Ever New Delight: The Pleasures of Paradise Lost,” Robert Crossley shows how Milton recast the Adam and Eve story in a new light. When God sent Archangel Raphael to visit Adam and Eve, Raphael kept arguing that Adam is superior to Eve and attempted “to turn the loving husband into a patriarchal boss,” but Crossley shows that “the Adam Milton has imagined is here asserting Eve’s ‘greatness of mind’ and natural nobility in the face of a doctrine of subordination.”

Because Eve overhears some of Raphael’s arguments, Crossley says this “creates a psychological context for Eve’s revolt.” After Eve fell, Adam faced the choice of falling with her or remaining obedient to God and living a life in his Eden paradise, but without Eve.

How can I live without thee, how forego

Thy sweet Converse and Love so dearly join’d

To live again in these wild Woods forlorn?

As Crossley points out, Milton explains in the headnote to Book IX that Adam “resolves through vehemence of love to perish with her.” In other words, the paradise Adam was unwilling to lose was Eve, not Eden.

In Paradiso, we are in a different paradise, not the Garden of Eden, but Heaven. In her book In the Margins, Elena Ferrante writes about Dante’s different portrayals of Beatrice in Vita Nuova and Paradiso. In the first, Ferrante says, Dante includes Beatrice among the “gracious women . . . who were endowed with understanding” but “could not sustain themselves on knowledge . . . because of ‘domestic or civil responsibilities.’” For Dante, his idea of Beatrice began to evolve and represent something new, something beyond “the gracious women.” According to Ferrante, at the end of Vita Nuova, Dante “[resolves] not to write about her anymore, until he had found a way to distort the old forms and to ‘say of her what had never been said about any woman.’”

Dante did so in Divina Commedia by making her an “unquestioned authority,” says Ferrante, “deliberately mixing the feminine and the masculine.” Ferrante describes it this way: “It’s as if she were saying: look at me,* here’s what I potentially was, and you didn’t understand the change in me . . ." This Beatrice overflowed with “scientific, theological, and mystical knowledge.” During a time when women’s roles were severely limited, Dante, says Ferrante, reimagined “what is possible for women.” In Paradiso, Beatrice is his intellectual superior, his mentor, his guide. Because of her, Dante was able to drink from the River of Light.

Likewise, B was all of the above for me** as she guided me through our Paradiso and showed me how our Heaven was firmly planted on this Earth. It was here that she taught me about the vehemence of love. Her fierceness gives me strength.

She was the Moon, and I reached for her like the tides. She was my mirror; she reflected who I am, or who I could become. I miss “what it was in her that made me more myself.”*** I miss her sweet companionship and steadfast reassurance. Amid all this loss, I remember that by the way she lived, she showed me how to embrace the here and now, knowledge I need now more than ever.

As I face a life lived in these wild woods forlorn, my wife’s lasting example is my guide.

Notes

* This sounds familiar.

** In case you are wondering, I told her such things sometimes, that she was my hero, that she saved me, but she always waved it off. She wasn’t big on attention or compliments, but once in a while, I wanted her to hear how I felt.

*** Julian Barnes

For some reason, maybe because I was writing about Eden, I remembered for the first time since the day we married that an instrumental version of “Morning Has Broken” was played at our wedding. My wife came from a religious family. Her father, a minister, officiated the ceremony. The music was religious, but my bride, the future children’s librarian, who was a rebellious sort but always in the kindest possible ways, chose a hymn by children’s author, Eleanor Farjeon. I have a hunch her fondness for Paradise Lost had something to do with her choice as well, plus that the song is barely religious, and though it evokes Eden, it’s really about spring in this fallen world.

A stealth, subversive selection. Praise with elation.

She was a wonder.

Beautiful, moving essay Wayne. Thanks.