A Sound Image

My student begins his essay describing what it’s like to tackle complex math problems. He shows his readers the pleasure he takes from the sound of the pencil scratching the paper as he works out a formula. It’s music to his ears. His senses are awakened. As Calvino said, “The image comes first.”

He came to love math because of a particular teacher who helped him to break down problems. The teacher focused on the process more than the solutions and did this by pointing out details and patterns that many often overlook. After this, my student caught fire, and it consumed him, causing him to enter what Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls “flow,” a state of mind where the process takes over and possesses you. The outside world disappears. Csikszentmihalyi‘s study is cited by Linda Flower and John R. Hayes when they compare “good writers” and “successful artists.” The writers and the artists become so absorbed in their task that they “delay in reaching closure.” They are “solving a different problem” than what other writers and artists are trying to solve. My student understands this. He calls the feeling of doing high-level math problems “phenomenal.” (There’s that word again.)

The English assignment was written by hand during a class session where I asked students to teach us about something they know well and to do so by allowing readers to be there with them during a specific moment from their experience with their topic. They were also asked to describe one of the tools or objects they had with them in that moment. After describing the scene, their task was to include some brief commentary on the thing they know and how they came to know it. The only rules? No introductions, no thesis statements, and try to fill up at least one page.

Embracing Knowledge

The math student defines knowing something as “being comfortable with a particular material” and feeling “free to embrace it.” Math had never grabbed him before. He could do it, but it was not that interesting. After his experience in that one math class, a change occurred. He’d solved a complex problem that he didn’t know existed—it was his lukewarm view of mathematics that stood in his way, not the subject itself. Now he reads math texts the way others read novels. It’s his idea of fun. To put it in composition theory terms, my student was describing how his “disposition” had shifted. He was writing about math but he was also writing about writing—he just didn’t know that yet. His math story was going to help him and his classmates get there.

His simple description of what it feels like to work out problems with a pencil and paper led to his excellent commentary on what it feels like to embrace a subject. It helped him to begin an investigation into how knowledge and expertise develop, an investigation that has the potential in later stages of the assignment sequence to go beyond the expected. And he did this in a forty-minute writing session without devices present.

For writers, you might be tempted to say that breaking down the problem is all that stuff about introduction/thesis, body, conclusion, etc. I prefer to break things down in other ways, starting with images and description and then with stages of revision. Let’s see how that works.

Is There Any Homework?

Why yes, yes there is. Let’s break down the problem by taking some notes. The following is based on an exercise Lynda Barry created for her drawing and writing class and published in her amazing book, What It Is.

Lists

Make a list of at least 3 topics that you know a lot about.

List a memory that you associate with each of those topics.

List a tool or object that you associate with each memory. (This should be an inanimate object, not a person or a pet.)

Do this with a pen or pencil on paper. If you have a favorite pen or pencil that is just more fun to write or draw with, use that. (And if you don’t, why don’t you?) Feel free to draw or doodle as you write. It helps you come up with the next thing.

Your Topic and a Connected Memory

Circle the topic from your list that speaks to you the most or that evokes the strongest memory. This is the one you will write about.

Picture a specific moment from your memories of this topic and write it down.

Answer the following questions about your chosen moment: Where are you? How old are you? What is the time of year and day? Why are you there? What are you doing and why?

What colors and shapes do you see? What do you hear? What do you feel or touch? What scents do you notice? What do you taste?

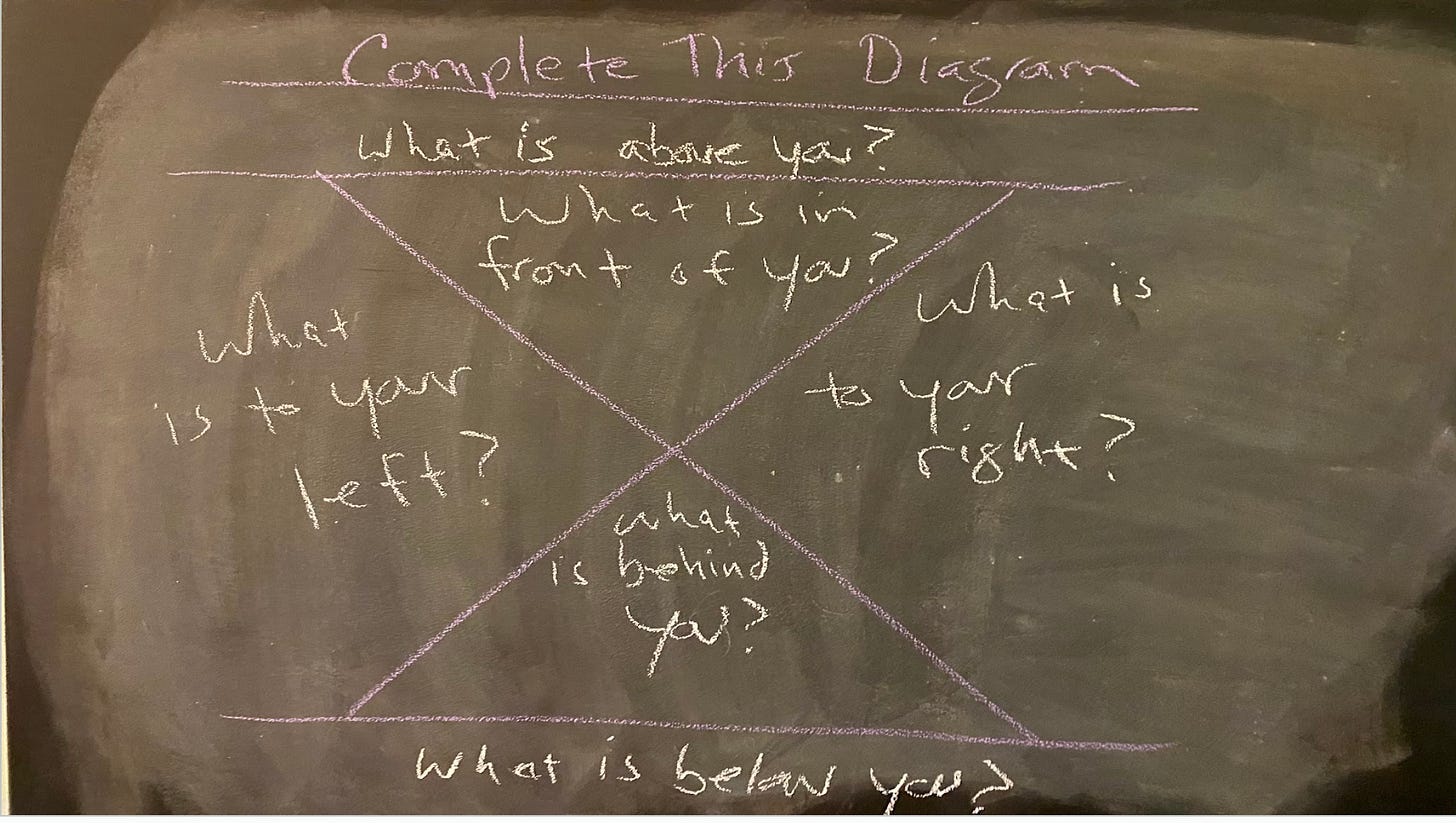

Writing Diagram:

Draw a Roman numeral 10 on a piece of paper and fill in the answers to these questions. Completing this diagram will place you (and your readers) in the scene you will be describing.

This note-taking session prepares students for the assignment where, like the math student, they will respond to a prompt while writing by hand with no devices nearby.

Writing Prompt: Something I Know*

Teach your readers about something you know by describing a specific moment connected with your topic.

Your story should include a description of an image or object that was part of that moment.

Describe by using sense and information details from your class notes to answer readers’ questions and to help them see and hear what you saw and heard—to help them feel as if they are there with you in the moment you are describing.

Before you finish, include some commentary on what that particular experience taught you about what it means to know something.

If you’d like to try this, give yourself a few minutes to go through the note-taking part, and then give yourself about 30 minutes to describe your specific moment and object without pausing to think. Just write like crazy, as Young-ha Kim suggests.

It’s likely that you will write something during that thirty minutes that surprises you. It’s also likely you will experience something akin to time travel. If you’re doing it right, you will no longer be where you are. You’ll be in the presence of a formless thing as it’s taking form.

Notes

*I’ve used other topics for this, like a time when you did something creative or innovative, a time when a particular environment affected you, a time when copying someone’s style or technique was beneficial to you, a meaningful moment from your life—lots of things will work.

Next time, we’re going to have to talk about your bad disposition.