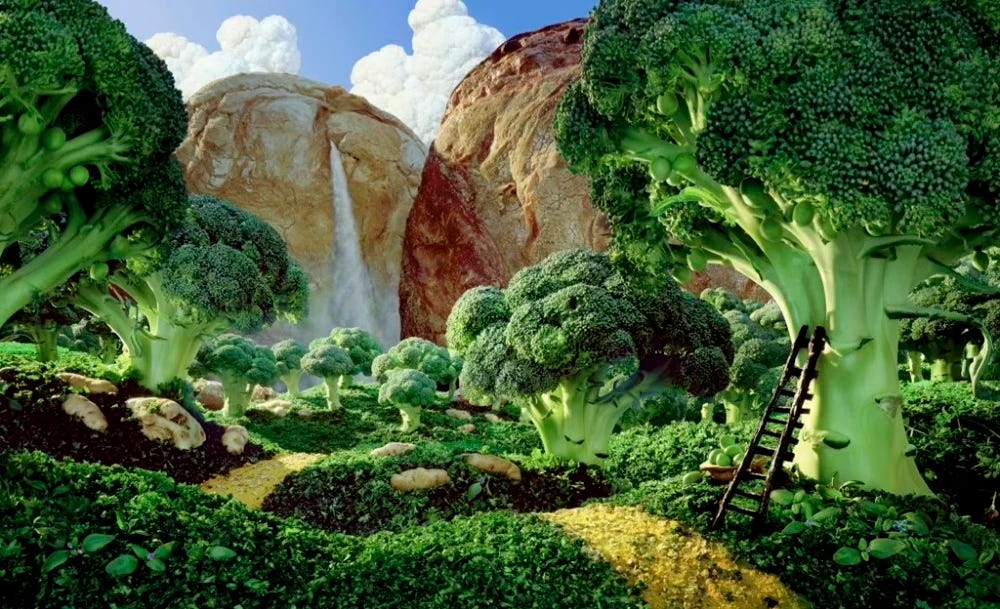

(Carl Warner, Broccoli Forest)

It was early spring. We were on the way to daycare and work. The sun shone brightly, and for the first time in ages, the air felt warm. “The trees look like broccoli,” our two-year-old daughter said as my wife and I helped her down the front steps.

My wife and I paused and glanced up. The maples that lined the street had transformed overnight. Wiry branches that had looked bare and frail the day before and for months before that now sported thousands of brilliant green buds that would soon burst out to form a canopy.

“Look at that!” my wife said. “They do look like broccoli!”

“They look delicious,” I said. “Let’s have them for supper!”

“Noooo!” said our daughter. “Eating trees is silly,” she added, setting her old man straight.

Earlier, we saw how metaphorical concepts influence perceptions. Simile holds similar power. The broccoli comparison is just the kind of thing a little kid might say—cute, but nothing more, you know, baby talk. Similes and metaphors have a bad rep. Yes, you can overdo it. Yes, they can be trite. Yes, things can get too flowery. As usual, that’s not the whole story. They seem simple, mostly insignificant, but a lot is going on. My daughter’s comparison is a good example.

I told this story to my students decades later. I knew there was danger in this because I would likely be peppered with unsuccessful smiles in future student drafts, but I was fine with that. It would give us things to work on and talk about, so I forged ahead. After recounting the scene to the class, I said, “If you’ve been around small children lately, you know they have lots to say. As time passes, you can’t possibly remember all of it or even much of it. Why do I remember this, even though it was long ago?” The main responses were that what we remember is mostly random, and this example is memorable because it’s cute. I conceded that there was something to both of these responses. I wanted to add to them. “Kids say a lot of cute things. We forget most of those, too. Why did I remember this random, cute thing?”

What really happened when my child compared newly budding trees to stalks of broccoli? The adults were in a hurry. The first thing the simile did was to make us slow down. We paused to look. If she had said, “Look, the trees are turning green” or “The leaves are coming out,” we would have said, “Uh-huh” or “That’s nice” and moved on. We may have taken a glance, or maybe not. It’s the oddness of the comparison that gave us pause—it made the familiar strange.

As Mom and Dad looked, what did we see? Something we’d seen countless times, but this time we saw it in a new light. Did the trees look like broccoli? Hmm, kind of, yes. We understood how our young child might think that. After the juxtaposition seemed to check out, something else happened.

When this childish comparison became part of our perception, then we were not simply seeing two unlike things as being alike, we were not only jolted momentarily from our habitual way of perceiving, we entered another consciousness, one where overnight, the world had transformed. Giant stalks of broccoli had replaced the trees that stood there the day before. Spring was preposterous! It was unbelievable.

We grownups, with our long experience of the seasons and our logical explanations for the causes and effects, surely already appreciated the changes spring brought forth. Our steps were likely a little lighter because of it. Yet the profundity of the moment didn’t sink in until our daughter spoke up. She was two. For her, spring was a brand-new thing. It was magic, wondrous. To Mom and Dad, though, it was a bit old hat. However, on that morning, because of a toddler’s comment, we were reawakened and rejuvenated like the trees. For a moment, at least, we lived in our two-year-old’s trees-like-broccoli world. Her simile got through to her audience so effectively that her audience felt what she felt. Her audience became one with her.

My daughter’s simile was not just baby talk. It was a complex thing, filled with resonances and implications. It not only made language livelier—it brought language and thought alive. Without the comparison, the trees would only be different. “Look, Mommy and Daddy, the trees look different.” “Yes,” we’d say as we rushed off to the rest of our day. “That’s because it’s spring. The leaves are coming out.” Our toddler’s comment would’ve gotten buried in the daily grind of our busy lives. Trees would remain trees, broccoli just broccoli, and spring would hardly change a thing. The comment wouldn’t stand a chance of being memorable. The moment would vanish into the deep past to join many other lost moments and the countless conversations we will never recall. The simile not only brought an ordinary scene to life at that moment but also gave it a future life where it resurfaces every time the trees turn green. That moment, thanks to our lovely daughter who with her words taught us what it’s like to feel new, became a part of us.

Of course, it’s not just two-year-olds who make such comparisons. In The Lives of a Cell, Lewis Thomas describes how a simile gave him a startling moment of clarity:

I have been trying to think of the earth as a kind of organism, but it is no go. I cannot think of it this way. It is too big, too complex, with too many working parts lacking visible connections. The other night, driving through a hilly, wooded part of southern New England, I wondered about this. If not like an organism, what is it like, what is it most like? Then, satisfactorily for that moment, it came to me: it is most like a single cell.

My initial fears about bringing similes into the mix with students were realized. Many cringe-worthy sour notes were scattered through their essays, so we either improved them, like Thomas, or decided some may not be needed in that particular context. We could talk about what worked or not and why and maybe have some laughs playing around with even sillier examples. Go ahead, have at it. This play will eventually add to our writing bag of tricks.

However, some of their similes were spot-on, even game-changing, like Thomas’s. Here’s a memorable one from ages ago by a student who said that before she learned the language, whenever she heard people speaking English, it sounded to her “like water boiling.”* Think of the typical ways she could have said that. “English was confusing.” “English made no sense to me.” “English sounded weird.” “It was just noise.” Yet with the three simple words she chose, for a moment, she turned all of her readers into English Language Learners.

The broccoli story gives a glimpse of language’s possibilities and its hidden, often untapped power. Similes and metaphors are not just baby talk and not just for adding spice to your writing—they’re a lens for changing focus and perception. They create new realities. A well-placed simile can blow your mind. One student described the effect as “going nuclear.” Some strange, awesome force gets unleashed in a flash. Writing then becomes more than words on the page. Now, it’s exponents ( or, “like” exponents). It’s (like) Galileo’s telescope, or a sketch of a tree in the notebook of a hopelessly seasick theology student.

Notes

*What I can’t recall is if she made that up or cited it as an example of a simile she’d read somewhere. Either way, it enhanced our discussion.

I’ve written about this before, now revised. It will likely be revised again.

Next, we’ll look at how metaphorical concepts can lead to or free us from writer’s block.

Farther along, we will spend more time talking baby talk.

Again, Ann Berthoff would have loved this!