1. The Dance: Writing, Teaching, Patterning, and the Danger of Models and Fortresses

On Keeping Your Convictions Fluid

[Writer-Type will be a series of reflections on writing and teaching and on writing while grieving. There will be occasional posts about fiction, typewriters, and multiple sclerosis.]

The Dance

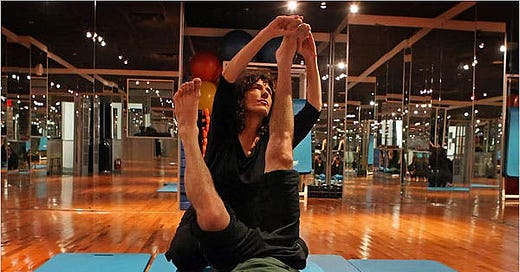

“Gravity was just taking me down. So my upper body . . . overcompensated, curling back and up.” This is actor Gregg Mozgala, a cerebral palsy patient, who learned dance with the help of choreographer Tamar Rogoff and dance partner Emily Pope-Blackman. Rogoff hoped to develop a small routine for Mozgala that might be within his capabilities.

Something else happened. New York Times writer Neil Genzlinger captured it when he interviewed Rogoff, who said that Mozgala fell whenever he “tried to move in a way that wasn’t specific to his habitual pattern.” This occurred, said Rogoff, "because he had a certain amount of patterning linked to his C.P., and I was asking him to step out of these patterns." To teach her student to dance, Rogoff had to learn his patterning and reflect on her own.

Such things come up again and again with writing. It demands we do things we can't do yet. In teaching and learning situations, teachers also ask learners to step out of their habitual patterns but sometimes without considering what this means, which can cause overcompensation and crushing failure. As a result, we "curl back and up." But in this case, says Genzlinger, student and choreographer worked together at "opening paths of communication” between body and brain, creating pathways “that had not existed."

Curiously, there were some things the teacher didn't want to know about her student. She didn't want much information about C.P. This way, she could keep from having fixed ideas about limitations. Without such preconceptions, she was free to meet Mozgala where he was and imagine what more he might do. Knowing the dangers of knowing too much and knowing when to shut off your role as an expert for a while may be key ingredients for successful teaching. This situation called for backing away from the problem to see it more clearly. Pope-Blackman, in her role as a dance partner, worked on discovering the right balance of push and pull in their dance routine. In this situation, the student, the teacher, and the partner are all learners.

Writers know this dance. They know that they must challenge themselves to do things that they can’t do yet, that they must break habits and recognize when they are overcompensating and when they are curling up rather than stretching out. But students often don’t realize this is normal. These things are uncomfortable and, in the wrong hands, play into our insecurities and anxieties and wound our self-esteem. Often, giving up seems like the logical choice. For many, no bullet list of pithy how-tos will get them where they want to go, just as the usual approach to dance instruction would not have worked for Mozgala, who needed instructors who could learn from him.

This series of reflections, inspired by the dance article’s lead, will explore ideas about writing in unconventional, sometimes counter-intuitive ways. To do this we will examine student writing choices to see what we can learn from those who are struggling to write. In addition, we will examine issues from inside and outside the world of English departments. Vladimir Propp wrote that in folk tales “usually the object of the search is found in ‘another’ or ‘different’ realm, which may be located very far away horizontally or at great vertical height or depth.” In these pages, I’ll follow suit and search in disciplines that don’t normally speak to each other—animal intelligence studies or saxophone instruction, for instance. The objective is to help writers break free from the conventional wisdom that may work for some but that sets traps for others and holds them back.

What? More Advice on Writing?

There are countless good books and articles about writing, so why write more? One reason is that as helpful as some traditional writing books are, there can be a certain patterning to them. Elena Ferrante says, “[W]riters too often talk about writing in unsatisfying ways.” Writing instruction can be a major writing block. What Ferrante says makes me ponder the overlooked fact that the usual advice and instruction won’t help everyone and that not everyone can be reached with oft-relied-upon methods. This, however, doesn’t mean such cases are hopeless and that breakthroughs are not possible. These essays will examine how my former, mostly first-year university students (who were mostly English Language Learners) have shaped my views on what is going on when people write. My students have taught me to continually reevaluate my thinking on the maddeningly moving targets of writing and teaching, sometimes making it possible for me to break old patterns.

Beware of Models

The problem with any academic discipline is that to teach, we try to pin our subjects down to a particular method or system. Like a butterfly under glass, the method may look pretty, but you don’t have to examine it too closely to see that it’s as dead as a doornail. Italo Calvino explores this dilemma with Mr. Palomar, a novel where the protagonist is struggling to comprehend how the universe works so that he can establish fundamental principles that connect all things (which, to be honest, is tempting to do with writing). He ponders subjects in excruciating detail, ranging from his lawn to waves at the shore, finally reaching the point in the chapter called “The Model of Models” where he desires “to construct in his mind . . . the most perfect, logical, geometrical model possible.”

Mr. Palomar is a Chaplinesque character, a hapless poor soul, one who’s never up to the tasks he has given himself, who bites off way more than he can chew, but you can give him this: He never takes the easy way out. Of course, his perfect model project turns out, as always, to be a never-ending, thankless task. First, it seems even if you design a cool model, the process raises unavoidable complications. When you tinker with one aspect, other aspects refuse to behave or hold still and resist being applied as neatly as you might wish. You find yourself, Calvino writes, “making gradual corrections to the model so it would approach reality, and in reality to make it approach the model.” Another complication Mr. Palomar recognizes is that “what the models seek is always a system of power” where they become a “fortress whose thick walls conceal what is outside,” which is a cautionary image for any academic to ponder.

Mr. Palomar concludes that “What really counts is what happens despite [the models].” This seems like a breakthrough moment and is the zone in which I often reside. But, damn it, even this could be a trap. Mr. Palomar frets, “What if all this becomes a model?” Mortified by this idea,

he prefers to keep his convictions in a fluid state, check them instance by instance, and make them the implicit role of his everyday behavior, in doing or not doing, in choosing or rejecting, in speaking or remaining silent.

After a While, Your Brain Maybe Gets the Idea

In this Palomar-inspired project, this poor soul is taking on a thankless task that’s definitely more than he can chew, but, as is easy to forget, that’s the fun part of writing. It’s where the action is. Even if you find you are not up to the task, fear not—you might discover that you end up in new territory where a different, potentially better project reveals itself (an essential writing characteristic lacking in AI, by the way, which seems incapable of straying from the thesis). As Octavia Butler said, “If you keep writing, after a while your brain maybe gets the idea.”

What’s happening when we write is elusive. Teaching is a tough nut to crack as well. We can learn some things from the people who are good at them and who have studied them, but even that leaves important things out. If we manage to gain some expertise at one or the other, we are in danger of devising “a most perfect model” that will become a fortress, eventually. Like Mr. Palomar, I’m most interested in what happens despite the models. Consequently, I resist the temptation to adopt any system too wholeheartedly and prefer to keep my convictions fluid—which seems to be what writing has been trying to teach me all along. (What my students also have been trying to get through my thick, fortress-like skull.)

In short, everything in this collection will be about writing—even when it isn’t. Now, let’s talk about ants and origami.

Notes

Genzlinger, Neil. “Learning His Body, Learning to Dance.”

Two books from Italo Calvino: Mr. Palomar and Six Memos for the Next Millennium